Finding Newness in an Ancient Staple

Pain d’épices, mince pies, pepparkakor, sticky toffee pudding, and speculoos. These are a few traditional delicacies made with the most prized ingredients that travelled along the early trade routes and into our kitchens during the chaotic lead up to the holidays. When my parents arrived in Canada as refugees from eastern Europe, they brought their own inherited customs, one of them the handmade and edible Christmas tree decoration that my sister and I valued above all. We could eat the soft and chewy confection sweetened with jammy syrup straight off the tree. And because szaloncukor is traditionally wrapped in crinkly foil, we’d untwist the fringed ends and slip the candy through, leaving the wrappers dangling from their branch, their hollowness discovered only when my father took down the tree in January. It was a thrill to delude ourselves that we had pulled off a genius and deceptive feat.

Not until I reached school age in our multiethnic community and started hanging out at classmates’ homes did I first encounter a mélange of spices and scents not of my own home but of distant, warmer places—places with sandy beaches and animal species found nowhere else on Earth. During the days leading up to the holidays, the sweet scent of ginger, cardamom, cinnamon, nutmeg, and cloves—spices with deep-rooted traditions—hung in the air in my friends’ kitchens. I fell hard for the unexpected newness that entered my world and the happy mingling with different cultures. Then, as now, these feisty spices are archetypal stalwarts of winter festivities.

So when I stumbled upon young organic ginger at the bustling Trout Lake farmers’ market some years ago, I was hurled back in time—not as far back as the ancient cultures that first cultivated the rhizome but to the sensual allure of my childhood friends’ kitchens, where I’d found myself holding two seemingly dissonant, but both delicious, cultural consciousnesses simultaneously.

This was like no ginger I’d ever seen before. Shiny and buttery translucent skins, with purply pink scales at the tips where the reedy stalks had been cut. I took home a few twisted clumps for an extra spike in my pumpkin recipes, savoury and sweet, and from then on have kept a cache from the annual harvest in my freezer, next to the emergency pâte brisée, both constants, awaiting times when I seek refuge in the kitchen.

Ginger cultivation is unexpected in the Pacific Northwest. Most of the global production of ginger is in Asian and African countries, currently known as a cultivar. How then did this perennial rhizome become a commercial crop in the farthest reaches of Abbotsford, B.C., where winter’s bite can sometimes get fierce?

Riyad Reid and his mother, Sharmin Gamiet, owner of Olera Organic Farms, trialled a small batch about seven years ago and have doubled the crop each subsequent year. “It has become more and more popular,” Reid says. “It started out as something experimental, which we tend to do on the farm.”

“I can’t even say when the end of ginger season would be. I want to guess end of October, but we finish with everything we’ve grown before we get to that timeframe.”

The challenge of ginger production in our Northern climate is that it requires a relatively long stretch—like, 10 to 12 months from planting to harvest. “It’s a time-consuming process,” says Reid. “In that same period, you could plant five different spinach crops in that same location. But we’re willing to take the time and to allocate the land for a nine-month grow period.” It follows then that this continuous use of land for the life cycle of ginger leads to a more costly product for the market consumer.

Young ginger does have a shorter shelf life than matured ginger. It’s also sweeter, juicier, and less fibrous. At Olera Farms, it’s handpicked on Fridays for the weekend markets. “There’s two things that I really like picking at the farm: ginger and basil, because I end up smelling like that for the rest of the day, which is always a good thing,” Reid says, laughing appreciatively. He recommends refrigerating the tender stems for 10 to 14 days before freezing.

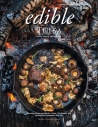

By far, the best part of the holidays is that we can be together, even if it means some of the decorations go missing. And sharing this soft gingerbread loaf (recipe follows on page 18), refreshing, unapologetically gingery, and scented with fragrant cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg that all play together so nicely, feels immensely connective. Not too sweet, it’s perfect for nibbling on with a cup of tea. In fact, I’ve come to believe that the holidays without it and the curvy knob of young ginger I pull from the freezer would be tantamount to heresy.

Olera Organic Farms

356 Defehr Rd., Abbotsford, B.C.

olerafarms.ca | @oleraorganicfarms