Peace and Pomegranates

As winter eases into spring, the perfume of hyacinths drifts over Central Lonsdale Avenue, mingling with the aroma of saffron from the kebab shops and fresh citrus from the bustling markets. Welcome to North Vancouver’s Little Persia, just in time for the Iranian New Year known as Nowruz.

Celebrated on the day of the vernal equinox (this year that’s March 20) for more than 3,000 years, Nowruz, which means the “new day" in Farsi, marks the first day of spring and the opportunity for a fresh start. More than 300 million people around the world take part in this festival of renewal, peace and solidarity, even when the world doesn’t seem so peaceful at all. It’s the start of two weeks of socializing and reconnecting with friends and family, gathering round the table to break bread (or at least enjoy some saffron rice) with the people you love.

And there’s no better place to celebrate Nowruz than here on Vancouver’s North Shore.

A taste of home

“Food will always bring people together. It’s why I love working in the kitchen. There’s no politics. The common goal is to make the most delicious food possible,” says Hamid Salimian, a former fine-dining chef who now teaches culinary arts at Vancouver Community College and is also a co-founder of the gluten-free Good Flour Co., a partner in Popina Canteen and a consultant for Earls Restaurants.

Salimian still vividly remembers the day his family arrived in Vancouver from Iran — November 11, 1989 — fleeing a country mired in political unrest in the wake of the Iranian Revolution of 1979. That was when the monarchical government of the western-leaning Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was overthrown and replaced by the theocratic government of Ayatollah Ruholla Khomeini. Under the new Islamic Republic of Iran, the shah was sent into exile and an estimated two million people left their homeland, including Salimian’s family. “I look back at what they did, leaving everything, and —” he pauses, at a loss for words.

Like so many others, they ended up in North Vancouver, mainly because his grandmother already lived here, but also because it felt a little like home. (Instead of the North Shore Mountains and Burrard Inlet, picture the Atlas Mountains and Caspian Sea.) “North Vancouver reminds a lot of people of Tehran,” he says. “It’s very similar to northern Iran. And in Canada, it’s the warmest area for sure. It’s a beautiful green land.”

Since then, North Vancouver, especially Central Lonsdale, has become home to a collection of Iranian bakeries, markets and restaurants. It’s a place to sample savoury grilled lamb kebabs and wonderfully chewy flatbreads, to pick up some freshly roasted nuts and a box of chickpea-flour cookies, to fill your shopping bag with rosy pomegranates, golden sweet lemons, jars of saffron and a fragrant potted hyacinth or two, to stop and gossip with friends old and new, perhaps over a cardamom-flavoured tea or a yogurt-based drink.

But all these decades later, even as a new year dawns, this community is still reeling from politics happening half a planet away.

A bittersweet beginning

On January 8, 2020, Ukraine International Airlines Flight PS752 left Tehran, Iran, carrying among its 176 passengers Ayeshe Pourghaderi, the co-owner of North Vancouver’s Amir Bakery, and her 17-year-old daughter Fatemah Pasavand. Shortly after takeoff, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, apparently mistaking the Boeing 737-800 for a missile, shot it down. There were no survivors.

Within hours, about 100 friends, family and neighbours had gathered, shocked and in tears, outside the bakery on Lonsdale Avenue. A few days later, hundreds more attended a candlelit vigil in the Civic Plaza. Three years after that, the community is still haunted by an act of violence that took the lives of 55 Canadians and 30 permanent residents, most of Iranian background.

The community has also been shaken by the death on September 16, 2022 of 22-year-old Jina “Mahsa” Amini. She was arrested by Iran's morality police for “improperly” wearing her hijab and died three days later, while in police custody. Since then, massive protests against Iran’s repressive regime have broken out in Iran and around the world, including here in Vancouver. All last fall, weekend after weekend, tens of thousands of demonstrators lined the walkways of the Lions Gate Bridge and the Stanley Park causeway and filled the downtown core, waving Iranian flags and signs reading “Woman Life Freedom,” the powerful slogan adopted from the Kurdish freedom movement of the late 20th century.

“For me, it’s very emotional. It’s very, very, very emotional,” Salimian says. “I am not a supporter of this government. If you look at what’s going on and you don’t have an opinion, you are not a human being. No person should treat another person that way.”

And so, as the New Year dawns on March 20, the season of renewal will have a bittersweet flavour. But it’s one that is familiar to the members of the Iranian diaspora because their homeland has always been a place of conflict. And the reason for that conflict, broadly speaking, is the same reason it has one of the world’s most exciting cuisines.

A cornucopia of cultures

Iran, Salimian explains, “is located geographically inside of a lot of countries.” (Iran is the official name of the country; Persia is the historic name used in the western world before 1935 and, nostalgically, by some today.) It is surrounded by, among others, Iraq, Turkey, Afghanistan, Pakistan and, across the Persian Gulf, Saudi Arabia. Thishas been good for trade — until the mid-15th century, the Silk Road brought goods and wealth through Iran — and has made the country a tempting target for invaders, including the Greeks, the Romans, the Assyrians, the Crusaders, Genghis Khan’s Mongols and just about everyone else.

“And every time someone comes by, they bring their food,” Salimian says. “It’s really beautiful to see it.”

There are ingredients and influences that landed in the area from as far as Northern India and Egypt. And within Iran itself, there are regional differences. The food made closer to the Persian Gulf is sweeter and spicier, Salimian says, often made with a sort of dry curry paste that goes into stews and rice dishes. “Then when you go to the north, they have a sour palate, so you get a lot of citrus and fruit molasses like plum molasses and pomegranate molasses.”

“Believe it or not, our cuisine is not kebabs. We have a very light cuisine,” he adds.

Traditionally, families would gather ’round the sofreh, a Persian fabric that served as the backdrop for feasts and celebrations and today symbolizes a place for family and friends to come together. The meal would begin with mezzes, small snacks that could mean cucumber salad, dips, breads, cheese, olives, nuts and little hot dishes, followed by the mains that often featured grilled or braised meats and scented rice, then something sweet to finish, perhaps served alongside black tea infused with cardamom.

“You would have 10 to 12 dishes for parties or four to five dishes at home,” Salimian says.

Nowruz, of course, has its own special dishes and customs, which vary in the more than 15 countries where it is celebrated, from Albania to Zanzibar, and by people of Islamic, Bahai, Zoroastrian and other faiths.

But in general, even before the festivities begin, there is often a major spring cleaning. People purchase new clothing and fill their homes with flowers, especially the hyacinths so ubiquitous on the North Shore. Then, at the exact moment of the spring equinox, families gather around the Haftsin table to start the new year. There are gifts for children, special decorations that may include mirrors, painted eggs, hyacinths and sweets. The celebrations can last up to two weeks, offering everyone the opportunity to visit family and friends over tea and pastries or to throw a big party with plenty of good eats.

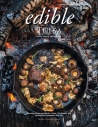

In addition to mezzes, Nowruz feasts might include fresh spring greens in dishes such as the frittata-like kookoo sabzi (see recipe on page 28), as well as whole fish fried with bitter orange, a sweet wheat pudding called samanu and braised lamb or goat served with dill rice. And if you’ve never experienced Nowruz or tasted Iranian food, one of the best places to get a taste of this rich culture is here in the markets and restaurants of Central Lonsdale.

Though it’s from a land rife with conflict, it’s still a delicious break from the world’s troubles, and a promise for a better year ahead.

“People ask, ‘What do you want for the New Year?’ ” Salimian says. “It may sound silly, but I really wish for world peace.”

KooKoo Sabzi

Recipe by Hamid Samilian

This herb-filled frittata-like recipe is a popular one to serve at Nowruz, and a delicious one any time.

½ cup cooking oil, divided, or 10 teaspoons unsalted butter, divided

5 green onions, thinly sliced

1 tablespoon dried fenugreek

1 tablespoon salt

1 bunch cilantro, stems removed, finely chopped

1 bunch flat-leaf parsley, stems removed, finely chopped

2 bunches dill, stems removed, finely chopped

3 large eggs

1 teaspoon baking powder

2 tablespoons gluten-free flour

1 lemon, juiced and zested

1½ cups walnuts, roughly chopped

¼ cup dried zereshk (Persian berries)

1 Seville orange

Preheat oven to 375 F.

Heat ¼ cup (60 ml) of the oil or 7 teaspoons (35 ml) of

the butter in an oven-safe skillet over medium-high heat.

Add green onions and cook for 1 minute, or until crispy. Add fenugreek, salt and herbs. Lower heat to medium and cook for 4 minutes, or until herbs start to brown.

Transfer cooked herb mixture to a large bowl to cool slightly, and reserve pan for later use.

In a medium-sized bowl, whisk together eggs, gluten free flour, baking powder, lemon juice and lemon zest. Add walnuts and zereshk to the bowl of cooked herbs, then stir in the egg mixture.

Return the skillet to the stovetop, add the remaining ¼ cup (60 mL) oil or 3 teaspoons of (15 mL) butter and heat it over medium heat. Add egg mixture to pan and cook for 2 minutes, until mixture starts bubbling. Transfer pan to oven and bake for about 20 minutes, or until the centre is firm.

To serve, flip kookoo sabzi upside down onto a large plate. Squeeze juice from orange over top and cut into 4 servings.