Cooking up a Story

Story by Linda Light.

My grandma’s grapefruit marmalade is one of our enduring family legends. She sold it door to door to support herself and her two children. Grandma was a genteel woman who studied elocution at finishing school, so the idea of her going door to door to sell her marmalade is hard to imagine. But “plucky” was a word often used to describe her, and plucky she was. Widowed when her children were tiny, she was a single mother before the term was invented. If marmalade was going to help support her and her children, she’d make a darned good one.

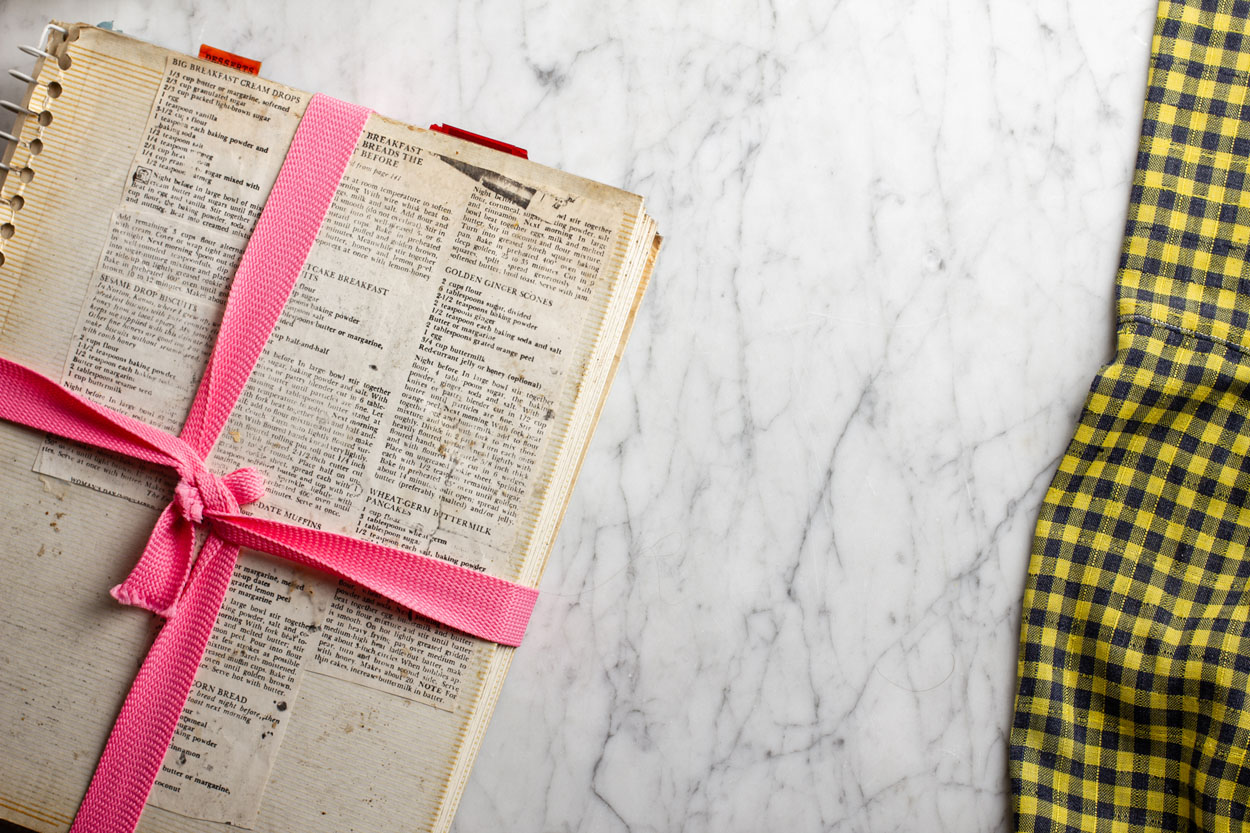

The original recipe for that marmalade is in my recipe book, written in my grandmother’s distinctive hand. I suspect my daughters will have to toss a coin for it after I’m gone.

But Grandma’s marmalade (recipe below) is not the only recipe in my book that has a story to tell.

Every recipe’s origin, every marginal notation, every remembered voice providing the soundtrack to an ingredient list is part of our family narrative. “Lisa’s favourite.” “Shortbread from Stornoway B & B.” “Don’t substitute marg for butter in this one.” “Use Heinz tomato soup for this.”

Auntie Marg’s toffee. A cup, a cup, three cups, a can. My sister and I can still recite that mantra a lifetime after we learned to make that toffee during our first summer holiday away on our own. We came home from the farm with the recipe in our heads and an eagerness to impress the family with our new-found culinary skills. For the record, the order of ingredients is butter, Roger’s golden syrup, brown sugar and sweetened condensed milk.

Then there are those indelible links between food and friendship. Marion’s mom’s sour cream cookies. Anne’s date loaf. Nancy Kleiber’s chocolate chip cookies. Annabelle’s clean-the-kitchen muffins. The names get passed on with the recipes from generation to generation until the friend is no longer known, the memory lodged only in the proportion of flour to butter.

Recipe books are full of all sorts of tantalizing mysteries. Who the heck was Mrs. Seaton, anyway? Three generations of children in our family have decorated Mrs. Seaton’s sugar cookies at Christmastime and none of us has any idea who she was. Our recipe for “Airplane lady’s red pepper pesto” has been served at parties for 25 years and all I know about this woman is that she sat next to my daughter on a flight back from McGill one summer in the early ’90s.

Some of the mysteries hidden in our recipe collections are more remarkable than others. For four generations in my family, we have fallen back on a flat, graham wafer-based chocolate “bar” for last-minute contributions to potlucks, bake sales and classroom parties. It can be whipped up on the stovetop in fewer than 10 minutes when a child suddenly announces at breakfast “We’re supposed to bring something for the Valentine’s party at school today.” Some of us call this lifesaver the bottom half of Nanaimo bar. Childhood friends still refer to it as “Mrs. Light’s flat cake.”

When my brother Googled my mom’s name recently, the following passage popped up in a paper in the journal Canadian Food Studies. The author, Lenore Laura Newman, works in the University of the Fraser Valley’s department of geography and titled her paper Notes from the Nanaimo Bar Trail.

“After searching 48 books drawn from archives in British Columbia and online, as well as gathered from local collections in Nanaimo, no reference to a Nanaimo bar or a similar recipe was found that predates 1952.

"[A] newspaper search was more successful. It was found that no recipe for chocolate fridge cake had been published in the Vancouver Sun before 1953, nor any recipe for a Nanaimo bar or similar dessert… however, two recipes were found for what is the bottom layer of the bar. On April 18, 1947, Mrs. Lois Light of Vancouver submitted a Chocolate Quickie Square, which she suggested be frosted with peppermint butter icing… and on Feb. 21, 1948, Jean Haines of Wildwood submitted a recipe for Unbaked Chocolate Cake that she claims is from New Zealand... If we then consider that the first recipe in the Sun for Nanaimo bars calls the middle layer a special icing rather than a filling, it becomes likely that the women of the [Nanaimo] hospital auxiliary created the Nanaimo bar by adapting the earlier cake recipe, inventing a new frosting and capping the dessert with chocolate. Though not impossible, it is doubtful that a recipe from before 1947 will ever be found…”

These seems to suggest that my mom’s flat cake was the first known recipe that led to the development of the Nanaimo bar. Who knew that all these years we had been eating a little piece of Canadian history?

My mother — writer, documenter, raconteur, cook, local historian — had never passed this extraordinary story on to any of us. Maybe she had no idea what part her “Chocolate Quickie Square” had played in the legend of the Nanaimo bar, an historical tidbit that would have tickled her.

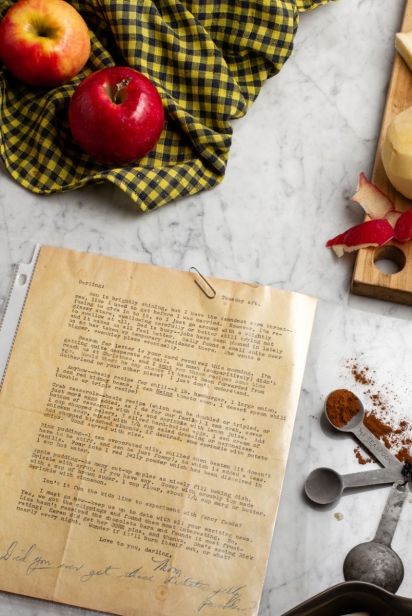

My younger daughter has my mom’s old recipe book. While many of those recipes continue to be family standbys, reading some of the classics from the ’50s and ’60s has caused much horrified laughter around our 21st-century dinner tables (apologies, mom, if you are still keeping an eye on us.) It is probably the jellied salads that cause the most hilarity: various combinations of sweet Jell-O, canned fish, condensed soup, mayonnaise and avocado that my mom served to her women friends at their cherished monthly luncheons. One of my personal favourites, from a historical perspective, is contained in a letter to me, dated March 3, 1965: “Chinese Luncheon Meat — as in Sweet and Sour Spam. With pineapple chunks.” My deep apologies to the Chinese. All I can say is that we loved it as kids and so did our motley crew in the co-op house where I lived when I was at university in Toronto.

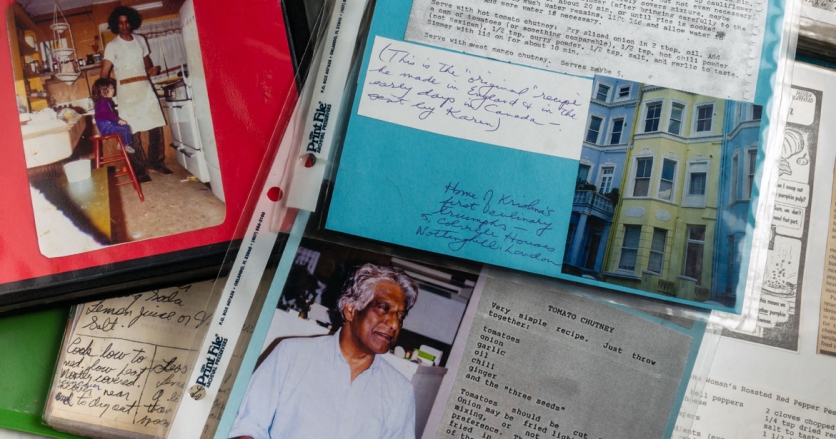

Our family recipes today reflect a very different reality. They started to change as each of us coupled. Krishna’s curries, dhal and biryani. Art’s lasagna. Ian’s beef jerky and Jamaican curried goat. Kelsey’s poffertjes and oliebollen. My mother was an early convert to fusion cuisine: once Krishna marinated the turkey in a yogurt-turmeric paste on Christmas Eve, she never looked back.

By the time some of these marriages had fallen apart, the recipes — and the partners — were so deeply enmeshed in the family that they continued to occupy permanent places at the family table.

My ex, Krishna, was the most legendary of our family cooks. But he rarely committed his recipes to paper. His measurements, much like his life, were based on instinct rather than conscious thought. When he died, it was the women who gathered his recipes into a collection, scouring his papers, our own recipe books, what he had shared with friends, our recollections as his sous-chefs.

And speaking of legendary, my mother always loved the thick Manhattan clam chowder served on B.C. Ferries. She loved it so much, in fact, that she wrote to the head of B.C. Ferries for the recipe. Although the chowder now served on the ferry appears to have no relation to the one that inspired my mom to make her big ask, the original version is still in our family recipe books. Mom called it Social Credit Clam Chowder, after the political party that formed government — and to which B.C. Ferries was accountable — at that time.

Our battered binders have much more to share with us than the secrets of a perfect pastry. (“It shouldn’t feel like Plasticine,” my mom reminds me in her familiar typeface each time I review her “pastry tips.”) They tell us about the history of our people and the worlds we have inhabited. That food is the way to the heart of a family. When to follow instructions and when to improvise. When to panic and when to laugh. When to tackle the impossible and when to take the easy way out. The importance of sharing. That some books are meant to be mapped with food stains.

They teach us about the importance of memory and of documenting our narratives. Essential as those marginal notations are to the recipe, they are even more important to the storyline of our lives. Above all, recipe books are historical treasures. These dear, ratty old binders document the times, family relationships, economic fortunes, gender relations.

The Krishnas of this world notwithstanding, family recipe books have traditionally been the domain of women. Their pages record women’s stories in ways that have often been obliterated by male historians.

Recipes may simplify dinnertimes and impress our friends, but they also bridge generations, link cultures, outlast relationships, make history — and give credit where credit is due.